This is an excerpt from The Future of Citizen Engagement: Rebuilding the Democratic Dialogue. Most citations have been removed but can be found in the full report. Select resources are included as links at the end of this post.

Practices by both the public and Congress have led to the relationship between Congress and the People being viewed as purely transactional, not the robust, substantive democratic engagement envisioned for a modern democratic republic. As the Internet, email, and social media have become more integral to the democratic dialogue, the tools and tactics used on each side have become more sophisticated, the volume of messages has grown, and the number of citizens communicating with Congress has increased.

As a result, both congressional offices and the organizers of grassroots advocacy campaigns are investing more time, effort, and resources in the communications. This has led to powerful frustrations in both Congress and advocates. Some congressional offices may be too inclined to mistrust organized advocacy campaigns, believing that the bad practices of a few represent the practices of the entire industry. Some organizers of grassroots advocacy campaigns may be too inclined to see Senators, Representatives, and congressional staff as uninterested in facilitating their constituents' First Amendment rights. These views are both far from reality, but tensions are high and the process is rife with misperceptions.

On the congressional side, the practices that have fueled a transactional approach to constituent engagement are largely related to capacity, communication, and technology, as discussed above. Senators and Representatives have so many constituents and comparatively few resources that they must prioritize who they engage with and how. Unless an office is highly strategic and goal-oriented, prioritization often comes down to being reactive to incoming messages and requests. Offices provide the greatest attention to those who participate. Despite their best efforts, Senators and Representatives tend to hear most from and engage most with people who have particular, niche interests—such as increasing funding to find a cure for a disease or decrease regulations in a single industry. These are the constituents most likely to be organized and politically active, but they are seldom representative of the entire district or state.

With Congress so focused on reacting to constituent demands, it lacks the resources for more thorough and methodical democracy maintenance. This can result in a Congress with an incomplete understanding of the range and totality of constituents' views and needs. It is important to note that this is not because Members of Congress are uninterested in the broader views in their constituencies, but because Congress does not afford the resources, time, technologies, and skills necessary to methodically collect and analyze those views.

Additionally, a significant percentage of Americans are disengaged. They are either uninterested in or disgusted by politics, or they lack the time or resources to connect with policymakers. Can one really fault a single parent working two jobs, who decides not to attend a telephone town hall meeting with their Senator, and instead focuses that evening on preparing school lunches for the next day? Regrettably, the needs of the disengaged are often different from those with the privilege of time, resources, knowledge, and confidence to engage with their Senators and Representatives. Unfortunately, the disengaged are also often the most vulnerable to decisions made without their input, which makes it all the more important for Congress to build the means and the will to proactively collect it throughout the legislative process.

On the constituent side, there is a lack of understanding about how and why to communicate with Congress. For many, civic engagement is purely transactional. Protests, one-click advocacy, and joining an organization that advocates on their behalf are the primary venues for many Americans to engage in public policy, but these are mostly viewed as "one and done" engagements. Once they participate in them, most disengage until they are prompted, often by anger, to perform the next transaction. Few follow up, and fewer still participate in the more sustained and deliberative democratic engagement that leads to change.

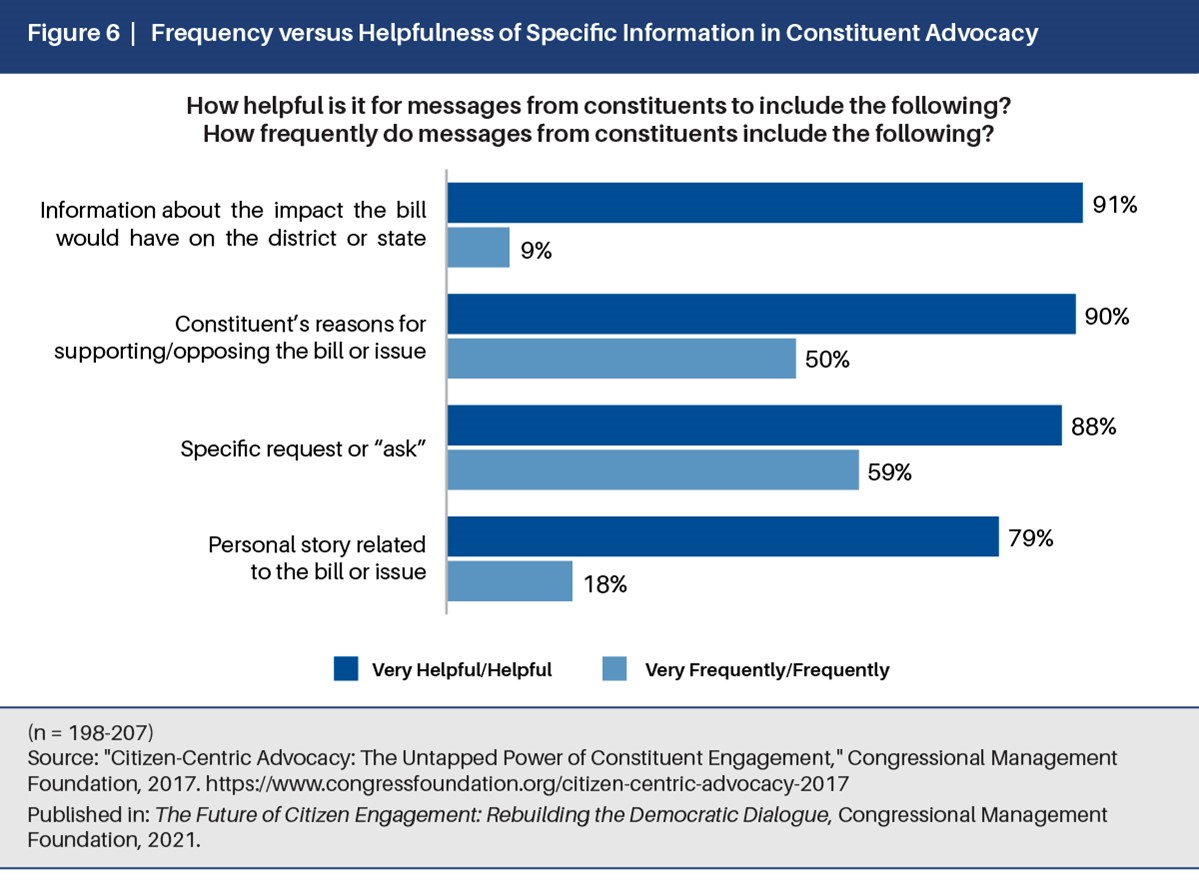

The most prolific source of messages to Congress is through "one-click advocacy." People are engaged in advocacy campaigns online through social media or other outreach or through encouragement by the organizations they belong to. For most people, this can feel like shouting into a void because neither the constituents nor most of the organizers of these campaigns truly understand what Congress needs or what sort of action or response to expect. As Figure 6 shows, these messages—usually form letters written by staff in the association, nonprofit, or corporation coordinating the campaign—seldom include the information that would be most helpful to congressional staff. As a result, they are usually counted and responded to, but they seldom substantively contribute to public policy.

More engaged constituents come to Washington, D.C. or Senators' and Representatives state and district offices for "lobby days" coordinated by the associations, nonprofits, and corporations to which they belong. Few understand or receive guidance on how to interact with legislators and their staffs and advocate for their positions, so they are ill-prepared for their meetings. Despite the fact that in-person meetings with Members and staff are the most effective means for constituents to have their voices heard, most fail to accomplish much because constituents usually do not have a clear sense of what they are trying to accomplish. In fact, only 12% of the staffers surveyed by CMF indicated that the typical constituent they meet with is "very prepared" for meetings with Members and staff.

In our 2021 report The Future of Citizen Engagement: Rebuilding the Democratic Dialogue, we propose ten principles for modernizing and improving the relationship between Congress and the People. All ten will require changes in the constituent engagement culture and practices in both Congress and the organizations that help facilitate grassroots advocacy. Principle 4 is that Congress must collect, aggregate, and analyze meaningful knowledge from varied sources, which this excerpt from the report helps demonstrate..

Additional Resources

- The Future of Citizen Engagement: Rebuilding the Democratic Dialogue (CMF)

- The Future of Citizen Engagement: What Americans Want from Congress & How Members Can Build Trust (CMF)

- Citizen-Centric Advocacy: The Untapped Power of Constituent Engagement (CMF)

- "Ten Principles to Drive Engagement with Congress" (CMF)

- "A Brief History of the First Amendment Right to Petition Government" (CMF)

- "The Place for 'Special Interest Groups'" (CMF)

- "Grassroots Advocacy and the First Amendment" (CMF)

- "Fake Comments: How U.S. Companies & Partisans Hack Democracy to Undermine Your Voice" (New York State Office of the Attorney General Letitia James, May 2021)

- Politics with the People: Building a Directly Representative Democracy (Michael A. Neblo, Kevin M. Esterling, and David M. J. Lazer, Cambridge Studies in Public Opinion and Political Psychology, 2019)

- "From Voicemails to Votes: A human-centered investigation by the OpenGov Foundation into the systems, tools, constraints and human drivers that fuel how Congress engages with constituent input" (OpenGov Foundation, 2017)

- Constituency Representation in Congress: The View from Capitol Hill (Kristina C. Miler, University of Maryland, Cambridge University Press, 2010)